The case of Leslie Arnold, a former Central student, went cold in 1967 after his elaborate escape from the Nebraska State Penitentiary. Fifty years later, Central alumnus Henry Cordes played a key role in solving the forgotten case.

William and Opal Arnold’s lives were taken by fatal gunshots at 6477 Poppleton Avenue in the fall of 1958. After his parents refused to let him take the car to a drive-in, Leslie Arnold decided to kill them and bury their bodies in the backyard.

“If that were really the case, there would be parents dropping dead in Omaha every weekend,” said Omaha World-Herald Senior Enterprise Reporter Henry Cordes. “I just knew there was way more to the story than the very shallow reporting that was done at the time.”

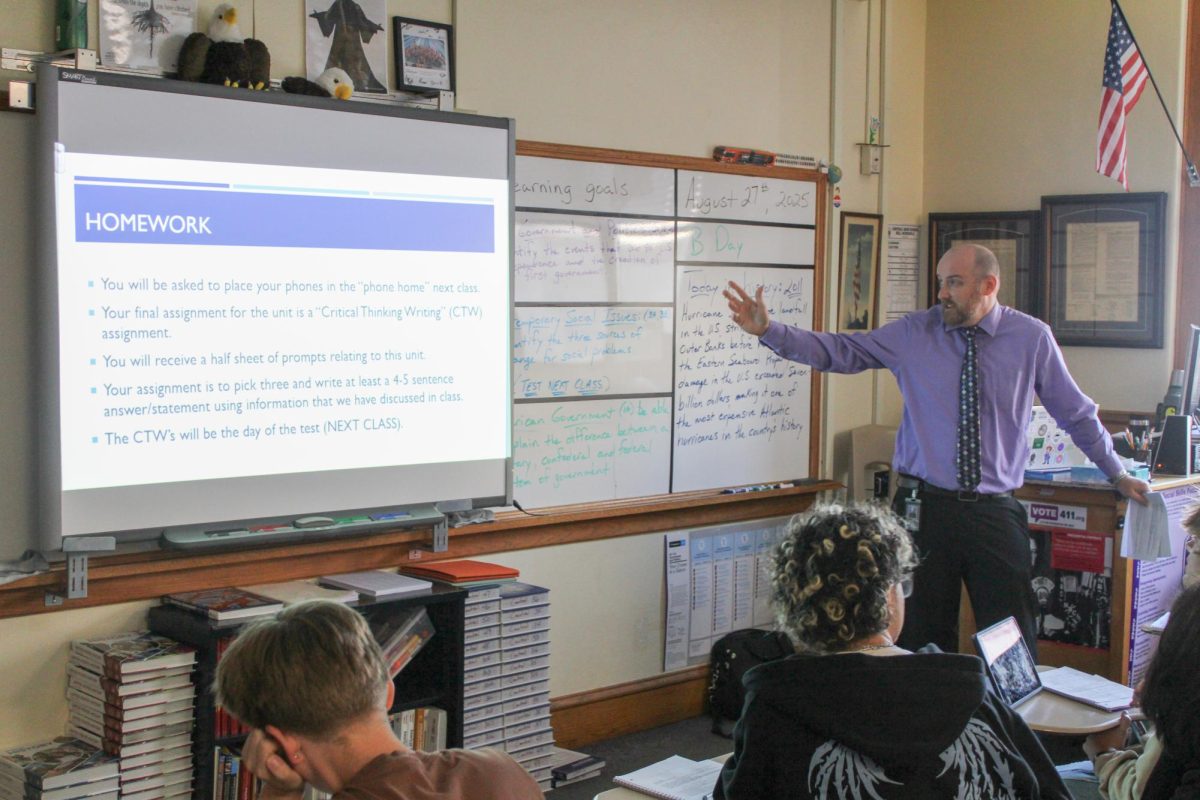

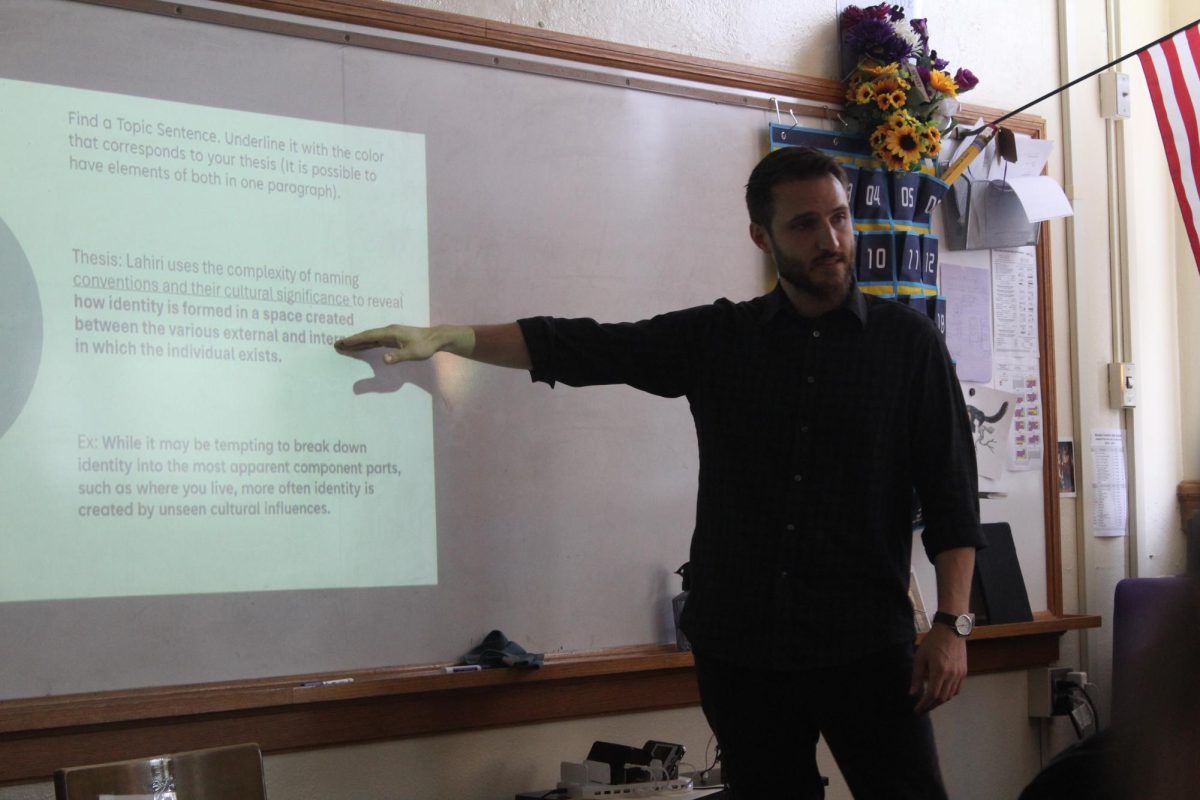

Cordes has been writing for the Omaha World-Herald for four decades and has been recognized as one of Nebraska’s most influential journalists. He joined the staff of the paper as a sportswriter months after graduating from Central. After graduating from the University of Nebraska at Omaha, he joined the news staff, covering crime. According to the Omaha Central High School Foundation, Cordes is a five-time winner of the University of Nebraska Lincoln’s Sorensen Award. He had a story in Poynter Institute’s book “Best Newspaper Writing”, and he has won multiple national awards.

“I was a Central student back when I first heard of Leslie,” Cordes said. “Leslie and I actually had kind of a lot in common. We were both young students at Central, living in the Aksarben neighborhood. We were both in the band. We were both on the track team.”

Though, the case did not strike his mind again until around 15 years later. Cordes was reporting at the capitol building in Lincoln, speaking to Ardyce Bohlke, a former member of the legislature. During their meeting, Bohlke told him the story of the Arnold family murders. Now, he could finally attach a name to the story.

He started by looking at old Omaha World-Herald clippings. After seeing the scarce reporting done at the time, Cordes knew there was a lot more investigation to be done. He decided to put the story in his idea file, a place to put story ideas that you want to end up reporting on.

It was not until 1999 that he started making some phone calls, talking to old neighbors who were telling him, “The mom was mentally ill, the kid had a temper, the mom seemed to really mistreat the boys and was very arbitrary in the way she dealt with him,” Cordes said.

“Right around the early 2000s, I met a cop who had a whole bunch of original records from the case,” Cordes said. “It included the evaluations the psychologist had given Arnold at the time of his arrest, and it went deep into the kind of dysfunction that was going on in the Arnold house.”

Around the same time, Cordes was able to get in contact with Jim Harding, the convict with whom Arnold had escaped from prison.

“He told me for the first time publicly how they had escaped, how they pulled it off,” Cordes said.

They had slipped through the bars they had sawed off, climbed a 12-foot-tall fence topped with barbed wire and ended up on a Chicago-bound bus, not to be seen again.

After visiting Arnold’s former classmates and house, going through old files and almost 20 years of research, the 50th anniversary of Arnold’s escape came around in 2017. Cordes deemed it as a perfect time to put everything he learned onto paper.

“I told my editor it’s now or never. That’s what became the series called, ‘The Mystery of Leslie Arnold,’” Cordes said. “It was a great story that ultimately would help lead to the solving of the case indirectly. The US attorney’s office in Nebraska, partly because of those articles, became interested in the case again. This agent named Matt Westover was assigned to the case in 2020. I was one of the first people he called. Nobody knew the case the way I knew this case, so it made sense for him to ask me questions about things he learned.”

In 2020, Westover got James Arnold, Leslie’s brother, to agree to provide a DNA sample to hopefully find a match, but they would not find a close match until 2022. It was Leslie Arnold’s son looking to find out more about his father, who he thought was an orphan from Chicago.

John Damon was Arnold’s alias. His new life started in Chicago, marrying a mother of four who waited tables. He became an independent traveling salesman and ended up living all around the U.S. He divorced, got remarried and had children of his own. His final destination was Australia, where he lived for 13 years before he died from complications from blood clots in 2010.

“I was excited as heck, for sure, about solving the case,” Cordes said. “I just couldn’t wait to tell people that I had this incredible knowledge, but I also felt a little bit of sadness too because this story has kind of become a big part of my life. I spent years looking into it, and I’ve always felt a personal connection to the story. Part of it, frankly, was the Central High connection.”