The first time Betsy Yadira Tenorio-Hernandez traveled between worlds was when she stepped into Honors Chemistry. After taking remote classes her entire freshman year, she entered her sophomore accelerated science class on her first day in person at Central to find only one other Latino student. “It was very shocking to me just because if you look at the school, you see more people of color,” Tenorio-Hernandez said, “but when you get to the honors classes, it’s very different.”

In her honors classes, she felt as if the world she knew with her family in South Omaha, one where everyone speaks Spanish and works construction or waits tables, was gone. In its place was the new world of her white peers, one in which parents are doctors or lawyers and the often harsh realities of immigrant life in America are unknown.

Soon, the hours she spent in honors classes became marred by a perpetual feeling of isolation. “I felt like I couldn’t really relate to them,” Tenorio-Hernandez said of her classmates. “We had very different perspectives and sometimes I felt like I couldn’t really speak out because my opinion was different because of my background.”

For Central High School, the diversity of its students is an essential part of its identity. “Pride in Diversity” is included in the school mission, emblazoned on a plaque hanging in the main office for all to see. With an attendance area that reaches from North O to downtown to Dundee, Central brings together students from extraordinarily different areas of the heavily segregated city it lies in the heart of.

But the diversity of Central’s student body is not reflected in its advanced classes, where affluent and white students are vastly overrepresented while students of color and economically disadvantaged students are consistently underrepresented.

Central offers three kinds of advanced classes: Honors, Advanced Placement (AP), and the International Baccalaureate Diploma Programme (IB), all of which require students to have signed parental consent to enroll. Students are selected for an advanced class either through a parent, teacher, or counselor recommendation.

AP is a national program that offers college-level classes to high school students, who receive college credit for their AP classes if they dual enroll at a local college or score highly on the year-end AP exam.

The most advanced academic track at Central, IB, is a two-year international education program for juniors and seniors based out of Geneva, Switzerland. Participants in the track are required to take seven IB classes every year, with students who score highly on IB final exams earning the IB Diploma.

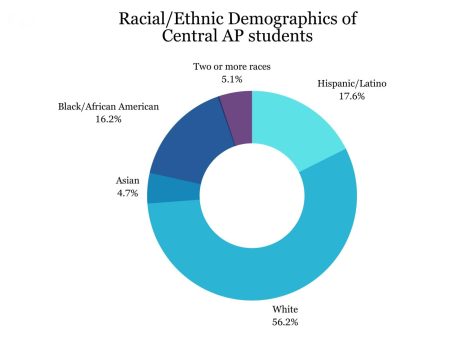

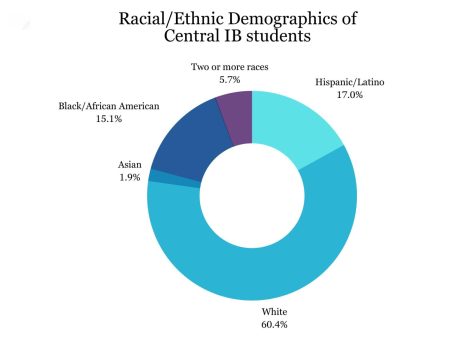

An analysis of student demographics by The Register, using data provided by Omaha Public Schools, found the percentage of white students enrolled in an academic track at Central increases at every level of advancement, while the percentage of students of every other race stagnates or declines. The share of economically disadvantaged students similarly declines in more advanced classes.

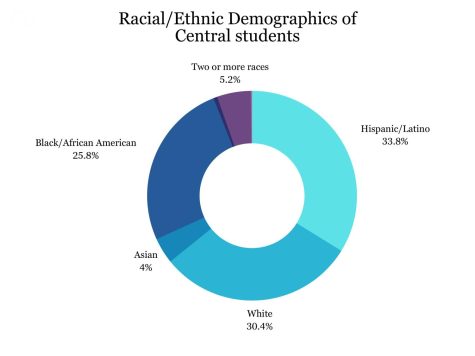

The largest ethnic group at Central are Latino students, at 33 percent, followed closely by white students at 31 percent. A quarter of students are Black, five percent are multiracial, four percent are Asian and less than one percent are Indigenous or Pacific Islander.

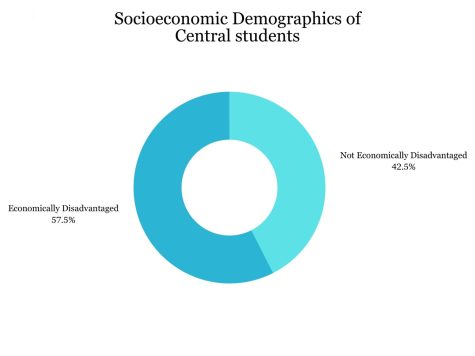

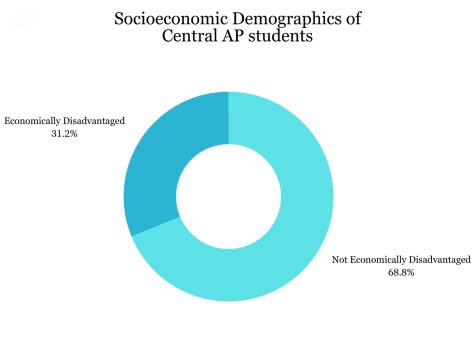

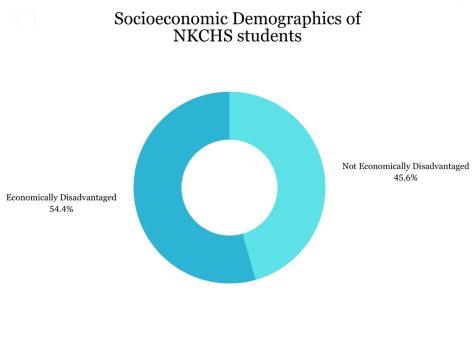

Over half of all Central students are also economically disadvantaged. The Register determined the percentage of economically disadvantaged students at Central by using data provided on the number of students eligible for OPS educational benefits, which include a free activity card, discounted internet access and fee waivers for testing and college applications. These benefits are available to students from low-income households, households receiving food stamps or federal nutrition assistance, students in foster care, as well as migrant, runaway, or homeless students.

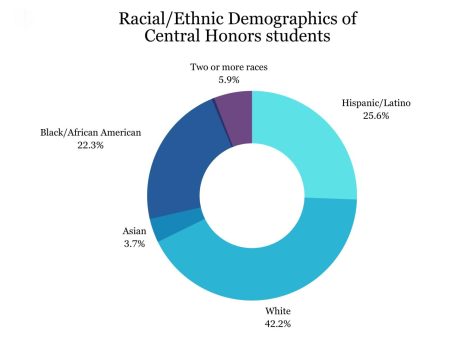

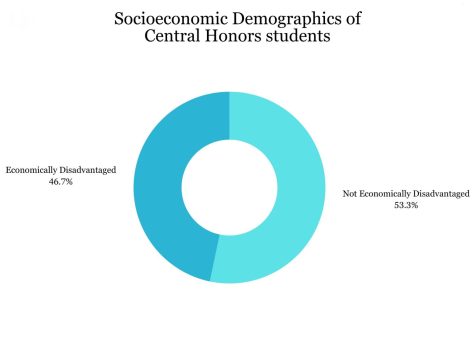

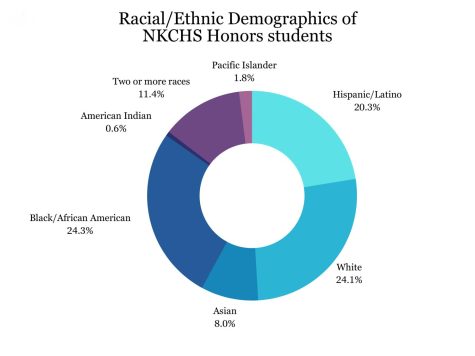

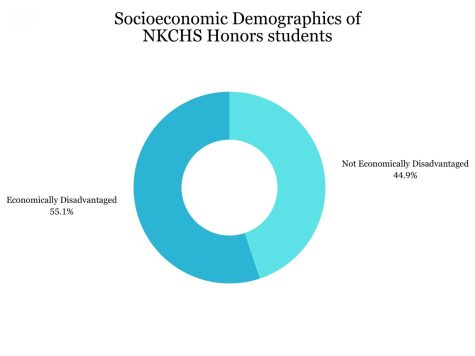

In Honors classes, the percentage of white students increases by 10% over their percentage of the overall student body, while every other race is slightly underrepresented. The percentage of economically disadvantaged students drops by 10%.

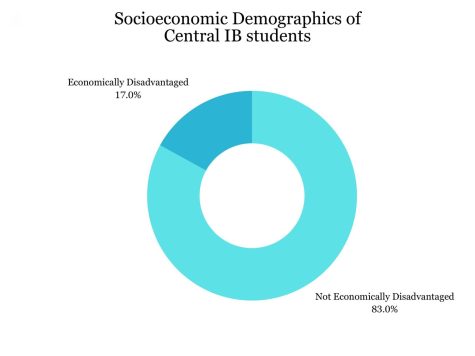

The most severe decline in racial and socioeconomic diversity occurs in Central’s college-level courses. The percentage of white students taking AP and IB classes is nearly twice the percentage of the overall student body, constituting a majority in both programs. Black and Latino students are underrepresented by nearly half. While the racial demographics of AP and IB are similar, they differ significantly in their socioeconomic makeup. Almost twice as many AP students are economically disadvantaged, at 31 percent, than IB students, at 17 percent.

Over 70 percent of white students at Central are enrolled in at least one Honors class compared to 47 percent of Black students and 40 percent of Latino students. And while 36 percent of white students are enrolled in at least one AP class, only 12 percent of Black students and 10 percent of Latino students are.

These racial and socioeconomic disparities are not unique to Central but remain a prevalent issue in advanced academics across the nation. According to the most recent data from the United States Department of Education, nearly 60 percent of students in gifted and talented programs are white compared to around 50 percent of overall public school enrollment. Only 8% of students in gifted and talented programs are Black, despite making up 15% of public school students. Latino students, who comprise 27% of public school enrollment overall, make up 18% of gifted and talented students.

However, the Register’s analysis of the student demographics of advanced classes in other high schools in the region suggests the disparities in Central’s advanced classes are especially glaring.

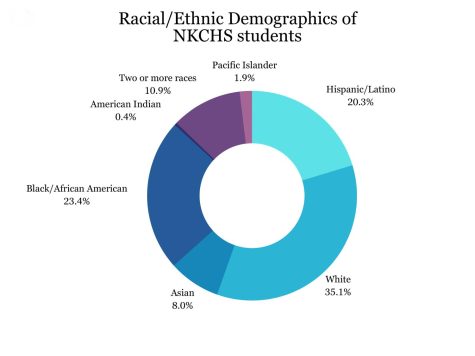

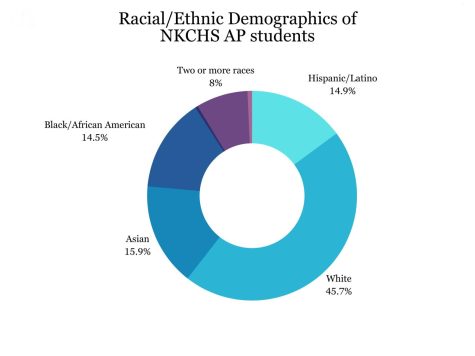

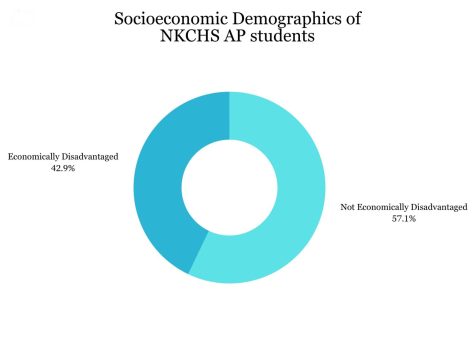

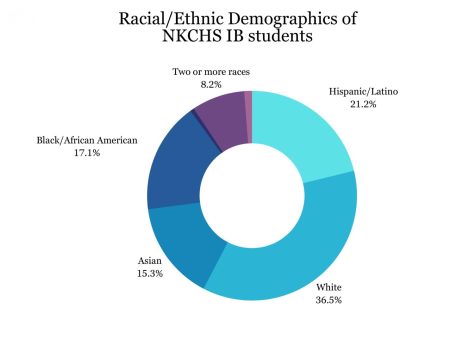

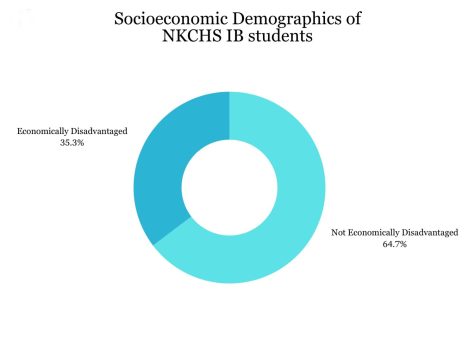

At North Kansas City High School, which also offers both AP and IB classes and has a similarly diverse student body, racial and socioeconomic disparities in advanced academics are still present but not nearly as pronounced as those found at Central.

Black and Latino students, who together comprise 40% of the student population, are proportionally represented in Honors classes, as is the slight majority of students who are economically disadvantaged.

In the AP classes at NKCHS, the percentage of white students increases by 10% and the percentage of economically disadvantaged students decreases by 10%, while the percentage of Black and Latino students both decline by 5%. In IB classes, white and Latino students are proportionally represented while Black students are only slightly underrepresented. Over a third of students in IB classes are economically disadvantaged, twice the percentage in Central’s IB classes.

Principal Dionne Kirksey said Central’s administration is aware of the disparities in advanced classes and working towards improvement.

“What we would like to see, based on our diverse population, is diversity in Honors, AP, and IB,” Kirksey said. “That’s what we’re striving for, but it’s an ongoing process. When it comes to disparities, you have to own the fact that it is there and you’re working at it. A lot of times people don’t want to have the conversation because when you have the conversation, people feel like they haven’t done enough. But with disparities, you have to be willing to have the conversation to make the change.”

Susan Christopherson, chief academic officer of OPS, said the district is addressing racial and socioeconomic disparities in advanced classes at all nine of its high schools. “We want to make sure that all of our programming is representative of our student body at all of our high schools,” Christopherson said. “We continuously meet with advanced academic coordinators from each school to review that data and help them to set some plans of action to help support within their own schools.”

Central IB/AP Coordinator Cathy Andrus declined to be interviewed for this story.

The racial disparities in Central’s advanced classes likely perpetuate inequality between white students and students of color in the school overall, as students in advanced classes can more easily access opportunities than students in standard-level classes.

Central uses a weighted grade point average on a 5.00 scale for students in advanced classes, while the GPAs for students in standard-level classes are on a 4.00 scale.

This weighted GPA system makes it harder for the disproportionately economically disadvantaged and students of color in Central’s standard-level courses to attend student life events only high GPA students are allowed to participate in.

Students must have a 3.0 GPA or higher to attend Winter Formal. Purple Feather Day, an annual celebration where students receive certificates and are released from their morning classes for activities on the football field, requires students to have a 3.5 GPA to participate.

But these disparities could have far worse consequences for Central’s disadvantaged students than missing out on a school dance, as research shows enrolling in advanced classes can improve students’ chances in later life.

A 2020 study by the Washington-based Education Trust found that high school students in advanced courses were more likely to graduate, go on to college and earn a college degree. A 2018 study published in the American Educational Research Journal found that students who dual enroll in high school received a college degree faster and with an average of $1,000 less debt.

“There’s clear evidence that being in an advanced class increases your opportunities to learn and get into a fancy college,” said Dr. Thurston Domina, distinguished professor in educational leadership at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. “Calculus, for instance, is just a hugely important gatekeeper for STEM fields in college. If you don’t take AP Calculus in high school, you could still become a doctor, but it’s much harder. So, these inequalities in education turn into inequalities in income and health for adults.”

Domina, who graduated from Central in 1993, is a sociologist by trade who studies the relationship between education and social inequality. His interest in the sociology of education was greatly influenced by his experiences as a Central student, beginning with his decision to take standard-level geometry instead of honors freshman year after doing poorly in algebra.

“I was the only freshman in the class, but it was a very diverse class, and the teaching was terrible,” he said. “For me, it was one of those moments where I began to understand it’s not really honors because it’s harder, it’s honors because that’s where the relatively privileged kids go to get better experiences.”

As a tenured professor, Domina now researches academic tracking, the process by which schools sort students into different learning environments and how this sorting shapes students’ life chances. Through analyzing the structure of education, he explores how schools, which theoretically offer equal opportunity to all students, actually reproduce the racial and economic inequality seen throughout the contemporary U.S.

“Affluent white kids disproportionately come out at the top of the pile at Central because the school is set up to legitimize their social position,” Domina said. “It’s giving a gold star to the people who are already at the top of the pile. But the school also has to launder that inequality. It has to make the unequal outcomes look like they reflect merit. So the sorting happens by creating these kinds of contests that appear to give everybody a chance to succeed, but almost necessarily create an outcome that looks a lot like the inequality that happened at the beginning.”

The origins of the disparities in Central’s advanced classes

Students of color are disproportionately sorted into standard-level classes at Central because of the many barriers they experience when attempting to access advanced academics.

The foundation of the disparities seen at Central is established in primary school, where the quality of education a child receives differs considerably based on the neighborhood where they reside.

Sophomore Iyanna Wise experienced the disparities in OPS’ elementary schools firsthand when her parents transferred her from Minne Lusa, a majority Black school in North Omaha, to Fullerton, a majority white school in West Omaha, halfway through her third-grade year.

“It was a completely different experience,” Wise said. “At Minne Lusa, I was one of the smartest kids in the school. At this new school, I was so behind. I was learning my multiplication, and at Minne Lusa, we were still learning our 10s. I go to Fullerton and they had already learned it. So, there’s that education divide in OPS, two completely different learning styles, and I was kind of a product of that.”

“My eighth-grade year, we didn’t learn anything in English or in Math,” said junior Eh Khu Poe, who attended Monroe Middle School in Benson. “My teachers were not professional, they would just like form cliques and gossip instead of teaching…going into honors classes, [white students] already had more opportunities, whereas I lacked opportunities just because I went to Monroe.”

When disadvantaged students reach Central, they may not feel prepared for or be fully aware of the advanced classes the school offers. This is worsened by a lack of knowledge among the families of disadvantaged students about how to support their children academically.

Affluent and white students are more likely to have parents who took accelerated classes in high school and can mentor their children through advanced academics, whereas economically disadvantaged and students of color are less likely to receive such guidance. This absence of mentorship disproportionately impacts first-generation students, whose immigrant parents frequently lack either the linguistic skills or experience necessary to help their children navigate an American public school.

“My parents really want me to succeed academically,” said senior Betel Aga, a Black student who immigrated as a child from Ethiopia with her family. “My parents support me financially and in other ways. What my parents can’t support me in are things like college, what classes to take, what clubs to do, because they’re not familiarized with the school system here.”

Senior Eli Calderon-Palacios, a first-generation Latina student whose parents immigrated from Central America, said she often struggled with her coursework as an IB student without parental guidance. “I have to do everything with my education by myself,” she said. “The students in my class who are white come from a background where both their parents go to college. As an individual whose parents didn’t even go to high school, it was hard for me to grasp onto all of this work. I didn’t have parents or siblings to help me figure out a math problem or how to write a paper.”

For immigrant and first-generation students who are not yet proficient in English, advanced classes are completely inaccessible. This is lack of opportunity is deepened by a sense of exclusion experienced by many English learners, who often feel marginalized by the rest of the student body.

“At Central, the students don’t talk a lot with you,” said Fawzia Mohammadi, an Afghan student who said she was unable to take Honors classes because of her English skills. “They are not friendly. If they talk in English with us, it will help us learn English.”

The sophisticated vocabulary used in the coursework of advanced classes can still be challenging for immigrant and first-generation students who are fluent in English.

“I still struggle with reading the documents,” said junior November Aung, a Karen student who took AP Language and Composition upon the recommendation of her sophomore English teacher. “It takes me longer to understand it and sometimes I feel like I don’t really have a grasp on all the ideas. There’s some difficult words that AP Lang uses that I struggle with.”

Students of color with the knowledge, confidence, and support necessary to pursue advanced academics must also be willing to spend most of their school day in predominantly white learning environments. Many students of color who spoke to the Register said they struggled to feel that they belonged in their advanced classes.

“When I was in standard-level classes with more diversity, I felt like I belonged,” said junior Maria Lopez-Lopez, who is in IB. “But when I started doing high-level classes, I was just there for the class. I can talk to my classmates, but I don’t really connect to them on a deeper level. They just have so much privilege and opportunities that I don’t have.”

In her sophomore year, Lopez-Lopez said her feeling of isolation, the difficulty of her coursework, and her involvement in extracurriculars all became overwhelming. She reached a breaking point and was planning to drop out before a friend convinced her to continue in IB, a decision she retrospectively feels was a mistake. “I do regret it because I feel like I would have made many more experiences [in standard-level classes],” she said. “It’s just hard to be in a class where you can’t relate to your classmates or have personal connections with them.”

Hafsa Osman, an AP student who immigrated from Somalia in 2015, said while she still can feel isolated in her advanced classes, they have become more welcoming as a result of white students becoming more open-minded. “Everyone here is not close-minded compared to when we were younger,” Osman said. “[In middle school], they wouldn’t mix with you or work with you, but now they will. We have all grown so much as individuals. Especially since 2020, the whole world has changed and become more aware of injustices.”

Senior Jaylin Sims said that she did not feel excluded in advanced classes at Central because she attended the majority white Alice Buffet Middle School in West Omaha. “I befriended those white counterparts and formed my personality around being that one Black friend that they had,” Sims said. “When I was at Buffett, my only Black counterparts were my cousins that were there. But they just weren’t in the same classes with me.”

However, Sims said her attempts to be accepted by her peers in advanced classes led to an identity crisis. “Who am I really, am I the token Black friend that my white counterparts want to see? Or am I the Black girl that my family wants to see and to be proud of? I had to go between those two and it just really hurt.”

Even if students of color are willing to enroll in predominantly white classes, they may still be discouraged from doing so by their peers. Many students who spoke to The Register said they experienced derision or harassment from other people of color because they decided to take advanced classes.

“People [of color] don’t want to join high-level classes, because they don’t want to be called whitewashed,” Calderon-Palacios said. “Because there’s this constant assumption if you’re a person of color and you’re in a higher learning environment, that you’re whitewashed, that you’re a white person because high-level classes are white.”

“I’ve always been called white girl because I’m a Black woman who is excelling,” Sims said. “When I was very little and they called me white girl for the first time, I’m like, ‘What about me shows white girl? I’ll change that right now because I don’t want to act like that.’ I wanted to get rid of all those characteristics, but I just don’t care anymore. I got away from it. Other Black individuals might not.”

Domina said these peer pressures have been recognized by scholars as a significant barrier to racial integration of advanced classes. “This whole sorting process I’ve described means the accelerated classes are white spaces,” he said. “It is not impossible for kids of color to find their way into those white spaces, but they pay a social cost for it. It feels to a community like you’re leaving your community when you go to those spaces.”

While one might expect that the diversity of Central would create more opportunities to form relationships between diverse groups of students, a wealth of research indicates the opposite is true. At diverse high schools with large student bodies, students are more likely to associate with people they already know than at smaller schools, which are likely to be people of similar racial and socioeconomic backgrounds.

Domina said that despite these social pressures, the “sorting process” which disproportionately places students of color in standard-level courses, can be interrupted by staff members.

“Every kid needs somebody sort of looking out and advocating for them,” Domina said. “Attentive teachers can make all the difference. I think counselors are particularly important in the way the school is set up now because they can direct people toward their spots in the curriculum.”

The lack of teachers of color at Central and throughout OPS was raised as an issue by many students of color, who felt that they could better relate to teachers of a similar background.

“If you have some white lady coming up to you, like, ‘Hey, come take Honors English,’ people may feel like it’s a white savior thing,” sophomore DeVon Richards II said. “So just seeing more minority teachers teaching those classes would be great. We do have minority teachers, but not a lot of them. So, if we had more of them teaching advanced classes I think people will definitely be way more interested in taking Honors.”

“Mr. [Andante] Lloyd, my history teacher last year, was my first Black teacher,” Wise said. “His class was way more relatable for me because we do have that similar background, as opposed to a white teacher. When Mr. Lloyd would make examples in class, I could relate to and understand them.”

For economically disadvantaged students, the intensive coursework of advanced classes may be difficult to balance with obligations outside of school.

“If you’ve got a poor economic background of any kind, it may preclude you from taking some of those courses,” said Dr. Ronn Johnson, associate dean of diversity and inclusion at Creighton University. “Often, you’ve got other things on your plate like working outside of school in order to help the family make ends meet, where individuals who don’t have that burden can focus their energies on studying and getting tutoring for those courses.”

The financial pressures placed on students from low-income households may explain why Central’s socioeconomic diversity declines the more advanced the curriculum becomes, with Central’s IB program having the fewest economically disadvantaged students.

“I do wish that teachers were more understanding when it came to a student’s personal life versus their academic life,” said senior Chloe Reese, a Biracial student in IB. “Personal situations have to be understood for students to succeed and contribute positively to the world.”

Reese said the demanding workload and stringent expectations of Central’s IB program often lead students to prioritize academic achievement over their mental health. She said these pressures disproportionately harm low-income students and students of color in IB who are more likely to balance schoolwork with personal struggles outside the classroom. “You’re expected to sacrifice essentially everything to excel academically,” she said. “To have like 20-page research papers and 4,000-word essays in all your classes and being treated like a machine is just very dehumanizing.”

Domina speculated the lack of socioeconomic diversity in Central’s IB program in particular was due to the location of its Middle Years program. The IB Middle Years Programme, which begins in sixth grade and extends through sophomore year of high school, teaches students the skills and knowledge necessary to be successful in the diploma program. Domina criticized OPS’ decision to implement the Middle Years program for Central at Lewis and Clark, a middle school in the affluent white majority neighborhood of Dundee.

“If it’s implemented well, [IB] can be a way to provide opportunities to more diverse sets of students,” Domina said. “It’s not uncommon, in the context of a district wanting to create more diverse school enrollments, to put IB [middle years] programs in schools in disadvantaged neighborhoods, in order to attract more affluent families and desegregate those schools.”

What Central is doing to close opportunity and achievement gaps for disadvantaged students

To redress disparities in Central’s advanced academics, Kirksey said the school administration has asked teachers to help identify students in standard-level classes with the skills and confidence necessary to excel in advanced classes. She also said the school has increased outreach to parents to raise awareness about the academic tracks offered at Central.

“I was that kid who was overlooked,” said Kirksey, who is Central’s first Black principal. “I never had an honors class when I was in high school, but I should’ve… I always want more kids to have more access. Anytime I can do something where it even makes a difference for one person, it’s worth it.”

With support from Kirksey and Central’s administration, several student organizations have emerged at Central over the past few years aimed at expanding opportunities for immigrants and students of color.

In 2021, administrators reintroduced Minority Scholars, a student organization dedicated to increasing racial diversity in advanced classes, which had been discontinued 10 years earlier. Founded in 1998 as the brainchild of then-Principal Gary Thompson, Minority Scholars offers additional academic and social support to students of color in Honors and AP classes. Students in the program meet during their lunch periods on A days to connect with other students of color in advanced classes and receive college and career training.

“We’ve had plenty of scholars that would have been fine going into an honors or an AP class,” said Social Studies Department Head Jimmie Foster, who co-sponsors Minority Scholars. “Other times, you need that extra support in those types of classes, so you can stick with it. That’s where Minority Scholars comes in.”

“I feel like Minority Scholars really helps,” said junior Artie Shaw. “It’s a place where we can kind of come together and connect with each other.”

Foster emphasized the importance of assisting students of color in developing the habits and skills necessary to excel in advanced academics.

“If you don’t have a kid ready for success, you’re just setting them up for failure,” Foster said. “I don’t know if just putting minorities in [advanced classes] for the sake of having minorities in would be practical or wanted. You want people to go where they’re going to have some success, while still being challenged. So are you doing the things beforehand to make sure that when they get to those classes, they have success?”

Latino Leaders is an after-school club that meets Wednesdays that aims to promote leadership, community service and post-secondary success amoung Central’s Latino students.

“I do think that because of their lack of knowledge, and also that language barrier that they have, they don’t necessarily think about it,” said Bilingual Liaison Anahi De la Cruz, who became the sponsor of Latino Leaders in January. “But, I want them to see that if college isn’t the choice, maybe trade school is the choice. If that’s not the choice, maybe you go to the army or figure out a way to create your own business or find a job that suits you.”

Since Latino Leaders includes students from every academic track, De la Cruz said that she assigned the students in advanced classes to tutor students in standard-level classes in subjects they struggle in. De la Cruz said she saw improvement in the grades and attendance of students who received tutoring from their peers.

Next year, De la Cruz said she hopes to increase outreach to Latino students in English as a Second Language (ESL) courses. “A lot of our ESL students right now are having problems with just familiarizing themselves with the school and feeling like the school is a safe place,” she said. “A lot of them are very confused as to where they fit in. So, I want them to feel like Latino Leaders is a spot where they can come to fit in and are always welcome.”

Thrive Leadership Club is an after-school program that meets on Tuesdays at Central that seeks to prepare disadvantaged youth, particularly immigrant and refugee students, for success after high school through fostering teamwork and English communication skills.

The club runs a mentorship program where recently arrived immigrant and refugee students are partnered with an academically successful student who has lived in the U.S. for an extended period.

“We try to match mentees with the right mentor, who can help them with their goals,” said Thrive Club Coach Said Saidy, who immigrated to the U.S. from Afghanistan six years ago. “I translate their assignments and their mentors can help them do it. They see how hard working [the mentors] are, how good they are at assignments and tests. A lot of the advanced students already know what they’re going to do.”

What more can be done?

The students and experts who spoke to the Register shared a wide range of different ideas on how Central could diversify its advanced classes.

“You have to think about outreach,” said Johnson, the Creighton associate dean of diversity and inclusion. “Even before high school, there’s a junior high that feeds into the high school. If you want to increase diversity, you need to create some kind of a pathway that will encourage diverse students to get involved in those programs. That message needs to start earlier and they need to get information earlier.”

Calderon-Palacios suggested that Central send students of color in advanced classes to diverse middle schools in its attendance area to inform prospective students about the school’s academic tracks.

“If they take at least like one or two students of color [in advanced classes], that would help,” she said. “Because I feel like if I was learning about it from another student of color, who shared the same traits as I did, I would be more motivated. I do feel like if you get them at a younger age, they start planning for the future and don’t just choose at the last minute.”

Tenorio-Hernandez urged Central’s administration to prioritize hiring more bilingual staff, emphasizing that otherwise, the school will be unable to inform parents who cannot speak English about the opportunities available to their children.

Until Central recruits more bilingual staff, Tenorio-Hernandez proposed that volunteers from Latino Leaders and Thrive Club could translate school documents, ensuring that written information about the classes offered at Central can be read by all students.

Wise recommended making Central’s academic tracks as flexible as possible, allowing students to move between them with greater ease. “Don’t just automatically jump from Honors Bio to AP Bio or keep doing regular classes,” Wise said. “I think there should be more opportunities in regular classes to make the switch to Honors classes when you’re starting to take the course and maybe realize, okay, this is a little easier.”

Some students expressed a desire for a more inclusive school culture, one which celebrates a variety of student accomplishments and is less fixated on academic achievement alone. “Be more open to everyone,” Reese said. “Don’t just focus on students who excel academically, also seek out students who are involved in their community, doing athletics, or involved in various clubs and organizations and showing that they care for things outside of academics.”

Sims recommended more resources be provided to students of color in every academic track, not merely those in advanced classes.

She claimed that racial disparities in education are worsened by an excessive focus on individual students of color who are academically successful, rather than striving to create more opportunities for all students of color. “They just pick one person of color who was successful in any state test, or anything like that, and run with it,” Sims said. “They see that one person who has a shade or darker than their white counterparts, not necessarily looking at the big picture, or the whole of every single person [of color] that can become successful.”

As part of her proposal, Sims argued that Minority Scholars should be expanded to include students of color in standard-level classes as well, saying that the college and career readiness it offers could benefit a wide array of students. “I think all students can use this information,” Sims said. “We actually have a lot of geniuses in the minority group. They just do not want to be surrounded by peers that do not look like them, so they fly under the radar.”

Domina suggested overhauling Central’s IB program to make it more accessible to the student body overall. “It is clearly not implemented in a way that’s consistent with the school’s values,” he said. “Having Pre-IB programs in other middle schools and being selective about where you place it, that’s one option. You could also create opportunities for kids to move into IB through summer programs before ninth grade.”

Domina also recommended Central allow more students to take IB classes without enrolling in the diploma program. Beginning in the 2022-2023 school year, Central students not enrolled in the diploma program were allowed to take IB Theory of Knowledge and IB Social Cultural Anthropology, but there is currently only one non-diploma student enrolled.

This may contribute to the lack of diversity in Central’s IB program, as most other IB high schools in the region, including Millard North and North Kansas City High, offer a broad selection of IB classes to students not enrolled in the diploma program. “There’s no reason why the IB classes need to be a walled garden,” Domina said. “If I can hop into an IB class without being a diploma student, that seems like a very easy fix.”

If Central’s college-level classes continue to be dominated by privileged students, Domina said administrators should consider getting rid of them altogether and reallocating the resources expended on those programs to improve educational outcomes for all students. “The question to ask about IB and AP is, can we do it in a way that’s egalitarian? For the longest time, the idea about equity around AP classes was to get AP classes and more of them into all schools so everybody had access to a school that had them. But in a school like Central that may not be the equitable way to go.”

Replacing existing Honors classes with so-called “Honors By Contract” classes, where students in standard-level classes sign up for additional work to receive Honors credit without being separated from other students, was also proposed as a way to include more disadvantaged students. “When you’re just in a regular class, there is that chance that there’s more people of color as opposed to an Honors class,” Wise said. “I think like having like a combo class and then just having people doing the extra work if they want that honors credit is way better for diversity than having separate classes.”

While those who spoke to the Register acknowledged actions taken by Central to alleviate disparities between students, many felt the school had a long way to go in addressing inequalities in opportunity and achievement for students.

“[Central] is trying in comparison to what I’ve heard from other schools,” said junior Sofia Rodriguez Arzaga. “There definitely is an attempt here. Every so often, I get an email from a teacher being like, ‘Hey, you’re in the top 20 percent of the class, here are some resources.’ But I do think that we could do better to actually close the gap.”

“It doesn’t have to be this way,” Domina said. “There’s so much amazing potential in a school like Central. It’s not easy to make a more equitable world. To ask these questions and to push on them is hard for schools and communities to do. These are difficult conversations, but they’re worth having.”