Do artists owe us new music?

I was lucky enough to see Virginian singer-songwriter Lucy Dacus in concert in New Haven, Connecticut at the end of September. This show was a part of Dacus’s last tour of her 2021 album, “Home Video.” Ever since she started touring, Dacus has devoted the last song of each concert to something unreleased. For her debut album, “No Burden,” she would play “Night Shift” which would become the most listened-to song in her catalogue. For tours of “Historian,” she would play “Thumbs” from “Home Video.” And for her tour of “Home Video,” she played an unreleased version of a song that will hopefully be featured in her fourth studio album.

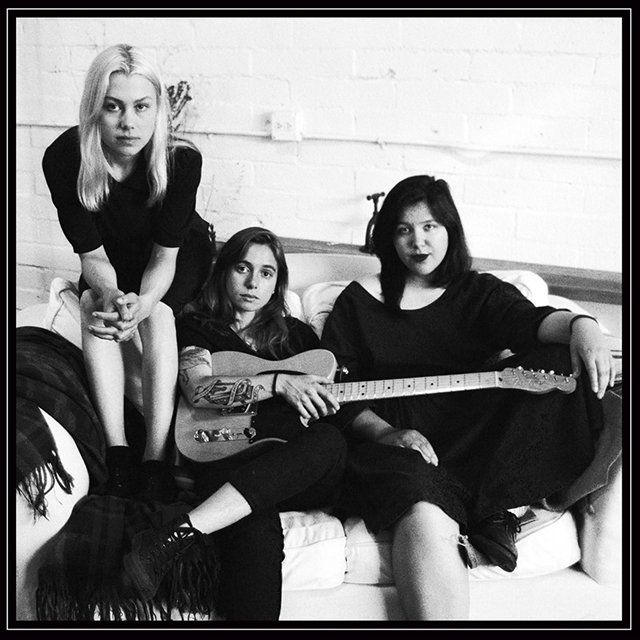

As an adamant Lucy Dacus fan, it’s always enjoyable to speculate about new music. Twitter accounts like @didphoebe provide daily updates on whether Phoebe Bridgers has released new music. While mostly for satirical effect — because most albums now predictably release on Fridays — the mere existence of these accounts shows that fans wanting new music from their favorite artists is nothing new. Now with the confirmed rumor of the indie-supergroup boygenius releasing at the end of March, insufferable sad people everywhere will be nearly bursting with excitement for new music. But rushing the creative process or skipping steps can create negative effects for both fans and artists.

On the one hand, it is human nature to continue the pursuit of something one enjoys. I will always love albums like Bridgers’s “Punisher” and boygenius’ self-titled EP. But listening to the same music repeatedly can get old. So, it seems only natural for people to want new music to grace their ears with from their favorite artists. People form “parasocial” relationships with artists (defined as psychological relationships experienced by audience members in their mediated encounters with performers in mass media) and feel negative emotions when left behind by their favorite artists without an album for years on end.

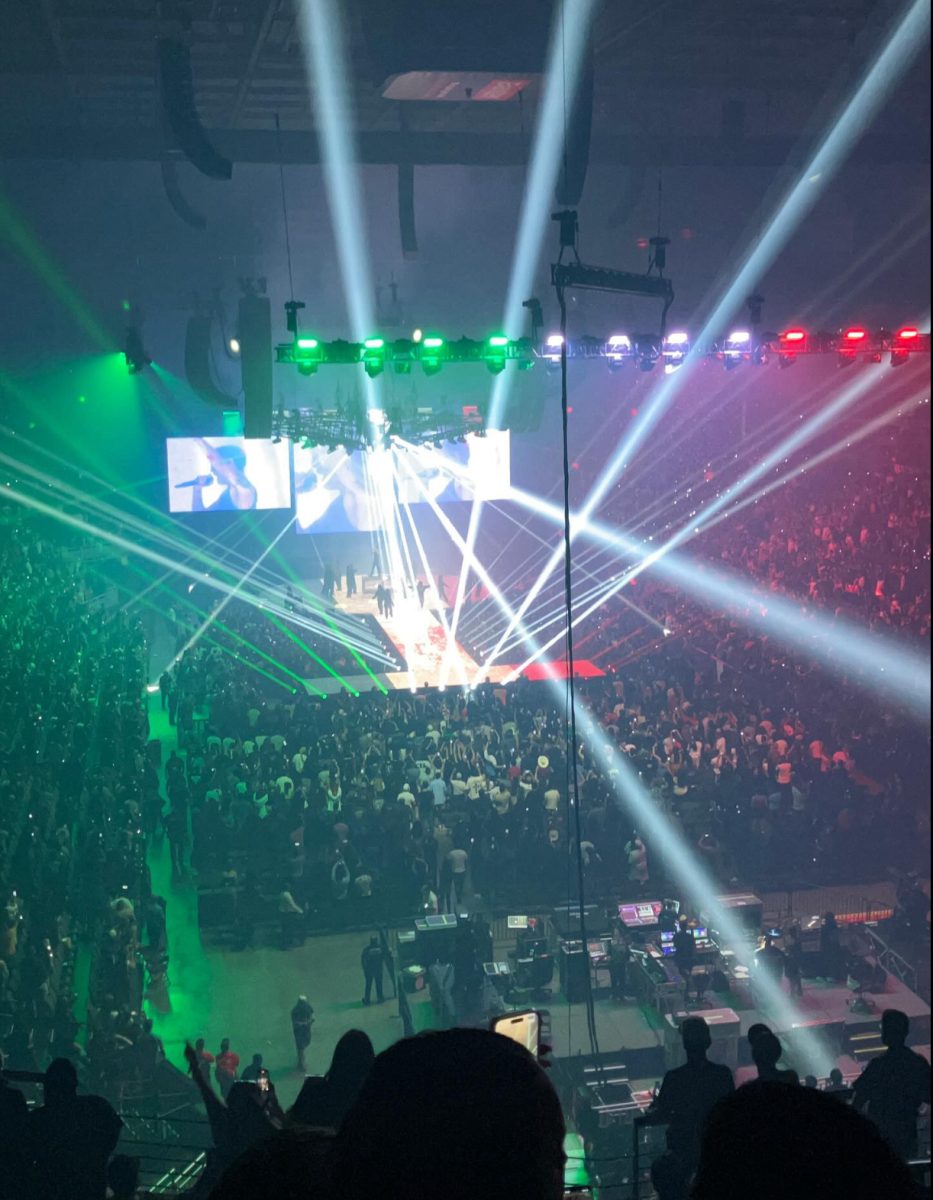

Many people, including myself, experience a type of parasocial relationship or interaction on a semi-regular basis. My favorite singers, writers, artists and speakers have no idea that I exist, but on some level, it does feel like I “know” them through their art. One of the largest examples of this phenomena is ARMY — the organized fanbase of K-Pop band BTS — a powerful entity that is tens of millions strong. It is hard to quantify how a group as large as ARMY sees a band, but it is almost impossible for BTS to recognize all members of the group as individuals, and it would be even harder to comprehend. On the other hand, artists who release music multiple times per year can tire out some listeners. Prioritizing quantity over quality certainly comes through in many cases.

In the end, all sides can feel like they are getting “the short end of the stick.”

While it is fun – and quite frankly not possible to stop – theorizing about new music, pressures from fans or otherwise conflict with the artistic process. The artistic process is completely abstract – there are no steps to it, unlike the scientific process, and it is not logical. But it is how we create. We cannot and will not stop theorizing, probably ever, but alas.

As Dacus says in “The Shell,” “Put down the pen, don’t let it force your hand.”

Your donation will support the student journalists of Omaha Central High School. Your contribution will allow us to purchase equipment and cover our annual website hosting costs.

Hi! My name is Charlie (he/him), and I'm a senior. This is my fourth (and final </3) year on staff, and I’m the Co-Editor-in-Chief. I was voted most...