Two students attest to lack of diversity in higher level classes

November 15, 2017

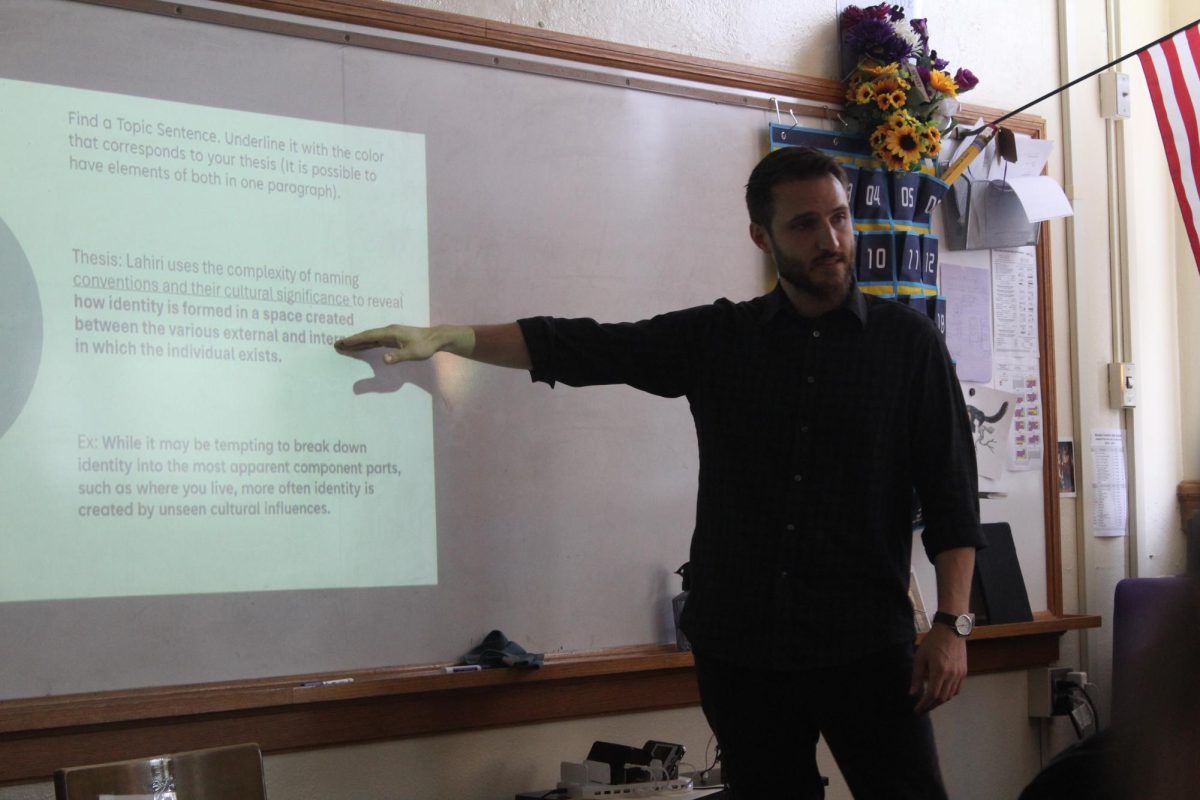

Senior Ra’Daniel Arvie has been a consistent AP and honors student for his entire high school career. Mariana Perez, a senior who started on a high-level academic track this year, is on her way to becoming the most educated in her family. They are excelling scholars and young people of color breaking the stigma associated with AP and honors programs, which despite the overwhelming diversity of Central, remains predominantly white.

“Central’s diversity is not well-represented in high-level classes,” Arvie stated. “In all honors or AP courses that I have taken at Central, I am one of two to three minorities in the class, and in some I am the only one.”

Perez seconds this, as she stated that her education can get lonely at times. “It’s not necessarily a bad thing, I think it makes me appreciate and understand things in a more personal way.”

As Arvie said, Central is one of the most accepting and diverse schools in the nation. Despite this widespread acceptance, he admitted that he is still faced with shock, disbelief or even anger from others that he could succeed over his white peers in the same classes. “Even worse, there are people in my classes who believe that, for some reason, they must talk down to me at some level that I’m not at,” he said. “At this point, it is just ridiculous.”

Self-segregation has long been blamed for these racial disparities in classrooms, and Arvie says that Central is no different. “Like most public schools, we tend to self-segregate. This mostly stems from students being afraid to meet different people and instead choosing an environment that they are used to.”

Perez agrees. “I think it’s more of a comfort thing,” she said. “The people who I hang out with understand what I’m going through, racially, so why wouldn’t I be with them? As opposed to someone who is, not in a bad way, but more entitled. What can I talk to them about, aside from things like the English homework?”

Solutions to these discrepancies are hazy and difficult to navigate, but Arvie believes that the administration should get involved, not by attempting to diversify classrooms directly, but by regulating the amount of schoolwork. “I know a plethora of minority students who I believe would excel in AP courses, but because of extracurriculars, they choose not to,” he said. “It’s infeasible for a teacher to believe that any student can go to school for seven hours, have practice or rehearsal for a few hours, deal with life itself, and somehow complete five or more hours of homework each night. That’s not even including a decent amount of sleep.”

Perez mentioned that there are many minority students who have to work in order to generate income for their parents and siblings. “I know kids in my community who have to work 50-60 hours a week to support their families, and for them, they just don’t have time for honors classes on top of that.”

There is no denying the statistical diversity of Central, but the interconnectedness of ethnic groups is often seen to be lacking. “There’s a lot of kids from all ethnic groups here,” said Perez. “But are we connected with our diversity? No. People stay with their ethnic group, their religious group, or with the people they’ve always known.”

As Arvie said, “We have a long way to go before we can truly call ourselves diverse, across the board.”