The Omaha Public Schools has embarked on its “moonshot” – an initiative to have every student reading on grade level by 2030 – but Central has not been able to offer supplementary literacy classes this year for students reading below grade level. However, a Science of Reading course is being offered to Central staff by the district to incorporate literacy skills into their teaching.

In the 2023-2024 school year, 65 percent of Central juniors were not reading at grade level, as indicated by the ACT.

Central used to offer classes for non-English Learner students who were one or more grades below grade reading level as they entered high school. Tier 2 instruction was offered to students who were one or two grades below grade level in the class Academic Literacy. More intensive Tier 3 instruction, for students three or more grade levels below grade level, was offered in Literacy Skills and Literacy Skills Year 2. English and literacy classes for English Learners are still offered at Central, and next school year, Tier 3 classes will be offered again. Plans for who will teach those classes are not finalized.

Students could begin reading classes as early as middle school after a combination of their MAP test scores, a teacher, or an administrator indicated the student may benefit from literacy support. A student might take the reading class for multiple years until their scores improve. From sixth grade to 12th grade, the classes are similar, involving an online reading program such as iLit, Code, or Read180, independent reading time and group instruction.

These classes are supposed to be taught by a teacher certified in reading, which is different than a certification to teach English. Currently, only two Central teachers are certified in reading, and they are both teaching other classes.

“Our biggest issue is just not having the right people here,” English Department Head Jonathan Flanagan said. “I feel supported by the district in terms of funding and training.”

A position for a reading teacher is open. Flanagan said not having enough English teachers is part of the problem, because English teachers could teach the reading classes, even without certification. Other OPS high schools also eliminated the program this year.

When the program was being offered, not all students estimated to read below grade level could be in a class. Flanagan, who previously taught Tier 3 classes, also said the classes work better with a small group of around 10 students, compared to the years he taught sections of 35. Next school year, the plan is for 101 freshmen to take the reader intervention course over six sections, Flanagan said.

In-class reading instruction and literacy skills, known as Tier 1 instruction, are taught in every English class. These skills follow the science of reading framework for teaching literacy, which is backed by science and focuses on phonics and related skills.

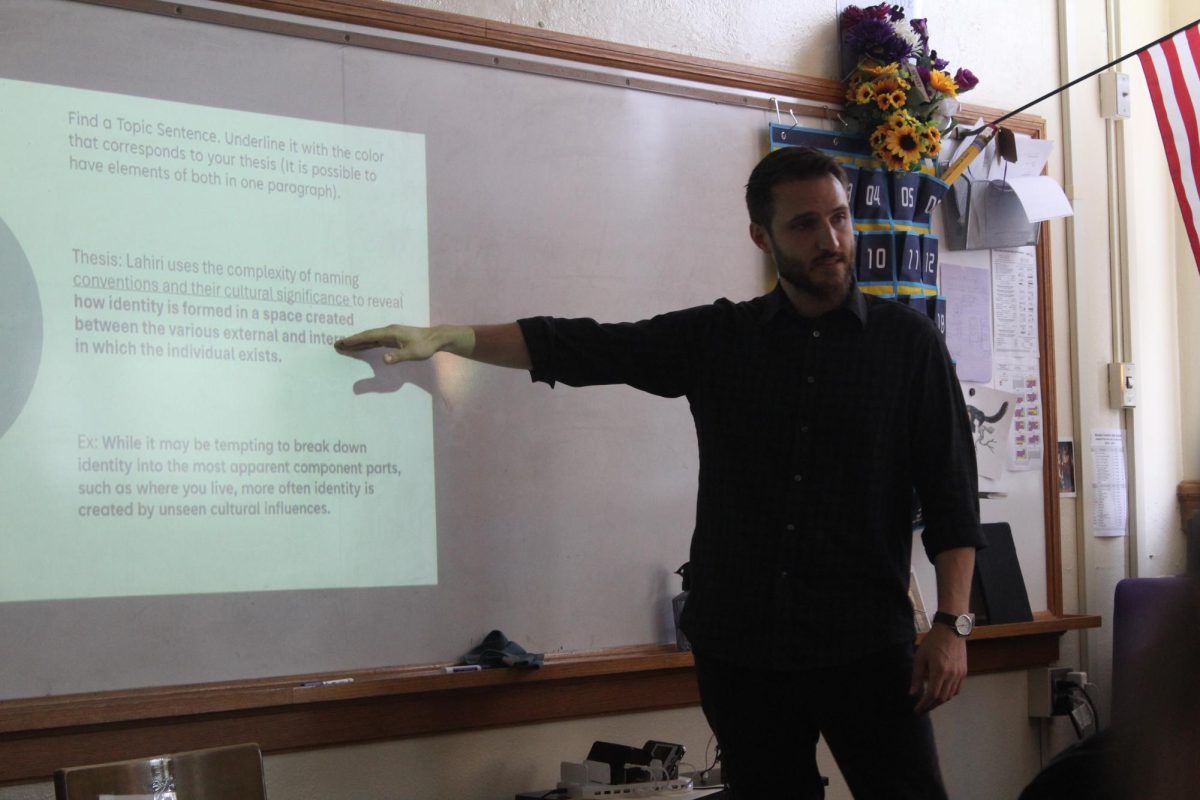

Beginning this year, OPS offered staff who teach sixth through 12th grade a stipend or graduate credit for taking a Science of Reading course and attending a collaborative capstone from TNTP, an organization focused on equity in education for low-income students and students of color.

“If [my students] are struggling literacy wise, struggling to read, struggling to interpret, it’s such a difficult thing of, how are you going to be successful in my class, in any class?” social studies teacher Ben Boeckman said. “I want to work on these literacy skills to improve my practice and help support my students more and more.”

The course covers barriers to literacy for different groups of students, the importance of phonics, teaching complex texts, and more. The course does not accredit a teacher in reading.

“I think it’s a valuable asset for everybody,” English teacher Molly Mattison said. “What I’ve experienced so far is this is stuff everybody really needs to know.”

Teaching literacy skills through the science of reading, or structured literacy frameworks, has not always been taught. Some reading instruction, such as the controversial Fountas and Pinnell curriculum, strays away from phonics and promotes cueing, or relying on context clues to read.

“We sort of didn’t teach kids to read for 10 to 15 years,” Flanagan said. “And we’re realizing, oh, wow, all these kids can’t read.”

OPS plans to collaborate with the University of Nebraska Omaha to train all secondary and some elementary teachers in evidence-based instruction by 2027. The district’s next steps are formalizing goals and ideas for the moonshot.

“I think we need to have serious conversations about what happens if students are not reading at grade level,” Mattison said. “What is the plan for students who are not reading at grade level?”