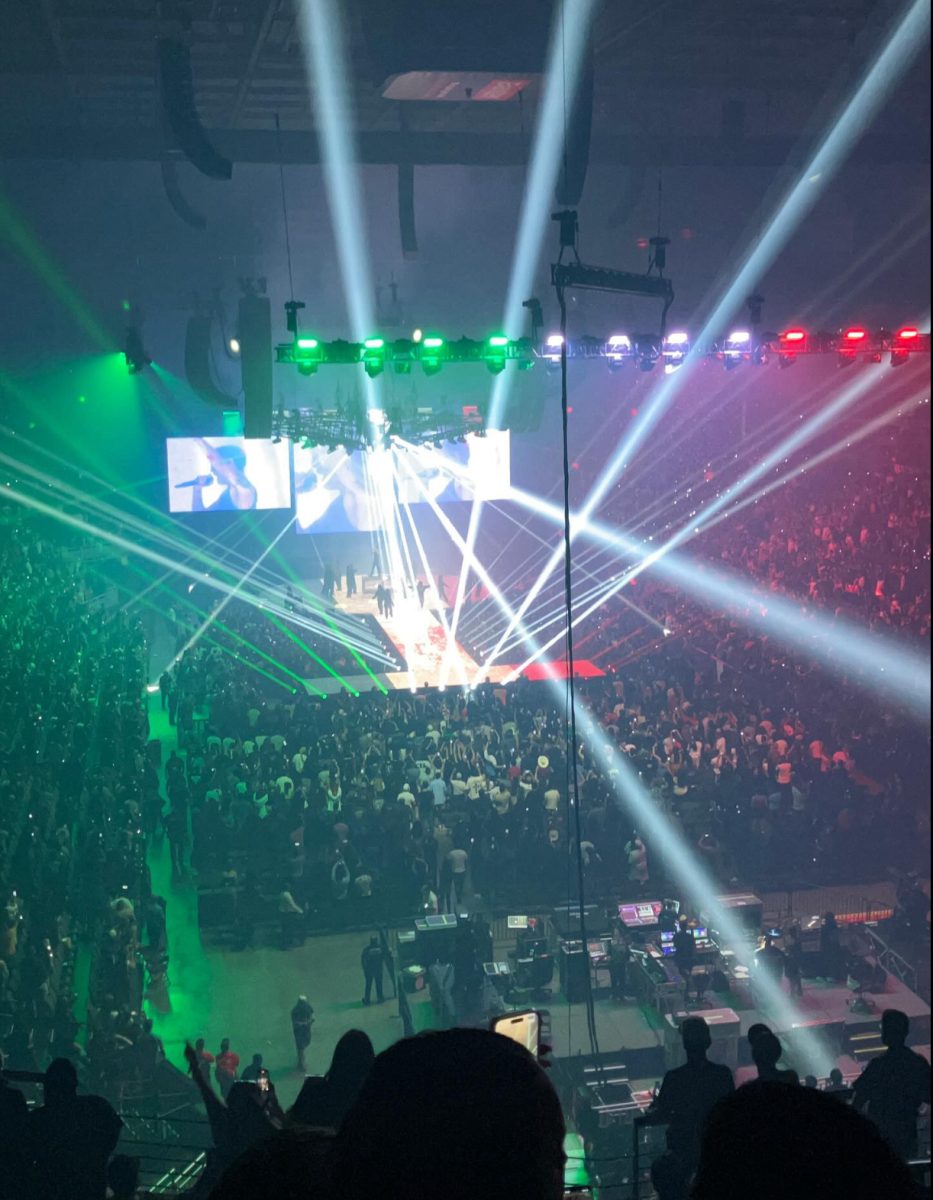

In an inconspicuous community center gymnasium on North 20th street, a vibrant sporting community was spreading its wings.

Oct. 28th marked the day of Omaha Roller Derby’s “Nightmare on Skate Street” Halloween mixer tournament. And a mixer it was – kids as young as 8 or 9 were competing on the same day as full-grown adults . Among the clashing nature of the scene were two Omaha Central students, both multi-year veterans of the sport: Evvan “Evanescent Echo” VanBeek and Quinn Wanzenried, a.k.a. Glitter Bomb. Both students have found the sport to be an inviting community space, as well as a place to express themselves.

Both VanBeek and Wanzenried explained that they started playing the sport because of a graphic novel they had read at the beginning of high school. “Roller Girl,” a novel by Victoria Jamieson, follows the story of a middle school student who survives her classes and social scenarios through the power of roller derby.

“She joins [a roller derby team] and dyes her hair blue, which is very symbolic for a derby player,” Wanzenried said. “She learns the skills, there’s a lot of drama and falling.”

VanBeek explained that their mother played the sport, which was another large pull towards the game.

The sport sounds, and looks, almost like a series of human fireworks. Wheels clang across the hardwood floors as people dressed in brightly colored clothing smash into each other, sending their opponents hurtling to the floor in an almost graceful fashion. Decorated helmets and dyed hair flash as the players zip around the track. Part track-and-field, part hockey and part wrestling, the sport is complicated to new onlookers. But after the nearly two-hour match, some things about the sport became clear to me.

The seemingly simple objective of the game is for the jammers to skate through a wall of opposing blockers. Four players form a team in the version that is played in Omaha: three people are positioned as blockers, and one person is the designated jammer. The job of the jammer is to lap the track, and break through a line of opposing blockers, who are sparring with blockers on the team of the jammer to jockey for better position.

Teams trade off two-minute “jams,” which are the periods where their jammers attempt to break through the opposing line. When one team’s jam ends, the other team’s jam begins, meaning the teams must transition quickly from offensive to defensive positions.

If the blockers are able to successfully block the jammer, the jammer’s team scores no points. But if the jammer is able to break through the line of opposing blockers (with the help of their blockers) the jammer scores between one and four points for their team. The jammer has several strategies to break through the line of blockers – jammers are typically short, which allow them to almost sneak through the lines of the opposing team; the blockers may also attempt to throw the jammer through the line of blockers, almost like a game of human bowling.

A typical roller derby practice includes lots of skating and conditioning, much like any other sport. Every two months, they do a practice where they need to skate a mile around the track in less than five 5 minutes. They start with stretches and warmups, followed in quick succession by a sprint.

“Because we have a lot of newer players, we’re really working on the skills,” VanBeek said. Practices don’t elapse without plenty of hitting, though. The physical nature of the sport prompts practices to get quite competitive, while at the same time maintaining the community aspect of the sport.

Beyond the sport, though, exists a rich culture of inclusion, community and frankness. It’s made evident through the concept of a “roller derby name.”

“Originally, they used to be a play on your name, which a lot of people still use,” Wanzenried said. “For me, I just really liked Glitter. I found a Glitter helmet, and I was like, ‘Tthat’s the perfect name. Glitter Bomb.’”

The derby name allows players to truly express themselves in a non-judgmental environment, which often doesn’t exist in mainstream sporting environments.

“It’s like, you have a pseudonym, you can be a different person,” Wanzenried said.

VanBeek added, “It is kind of like you’re a whole other person [with your derby name], but not a whole other person. It’s almost like superheroes with their secret identity kind of thing where you gotta be confident and cool.”

“I use Glitter for everything, but Glitter Bomb is when I’m confident and hitting people. I can never do that off-skates,” Wanzenried said.

The pair said that derby names are especially important for people who feel like they can’t be who they are around their family. They both attested to derby being a safe space.

“Derby is like a family. We’re all really close and we all share absolutely anything with each other. We don’t see each other outside of derby, so they can’t really judge you,” Wanzenried said.

“Derby is the embodiment of that one aunt that you see rarely but she’s like the coolest person ever,” VanBeek said.